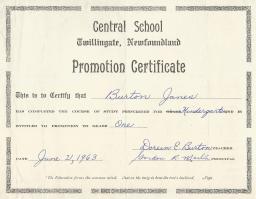

I did Kindergarten in Central School in Twillingate in 1962-63. My teacher and principal were Doreen E. Burton and Gordon R. Martin respectively. By then, the Royal Readers had long since disappeared from the education system. My late parents, who had used them as part of their schooling, told me and my siblings about the books. I often wondered if I would ever possess my own personal copy of at least one of them.

I did Kindergarten in Central School in Twillingate in 1962-63. My teacher and principal were Doreen E. Burton and Gordon R. Martin respectively. By then, the Royal Readers had long since disappeared from the education system. My late parents, who had used them as part of their schooling, told me and my siblings about the books. I often wondered if I would ever possess my own personal copy of at least one of them.

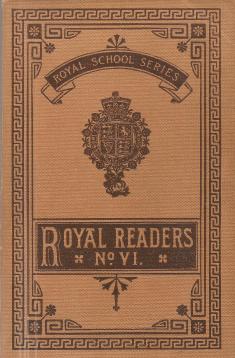

The series of eight books were produced in Britain by Thomas Nelson and Sons and were part of the Royal School Series. They were used in Newfoundland and Labrador from the 1870s until the mid-1930s. Students–or “scholars,” as they were invariably known–progressed from the infant reader to the school primer, followed by Royal Readers one through six. They covered reading and spelling from the beginning of school to graduation. The stated aim of the series was “to cultivate the love of reading by presenting interesting subjects treated in an attractive style.”

The infant reader was comprised of rhymes and simple short stories, accompanied by numerous illustrations. There were also short script lessons and addition and subtraction tables. Emphasis was placed on systematic drills on vowel sounds and consonants.

Scholars learned letters and reading from the first level school primer, which was similar to a primitive kindergarten.

The first Royal Reader begins with simple lessons, focusing on monosyllabic and two-syllable words. The second reader includes short selections of poetry and prose intended to develop reading interest and skills. Each story is accompanied by a pronunciation lesson, simple definitions of new words, and questions on the content. The third reader, which is slightly more advanced, includes more writing exercises. The fourth reader includes phonetic exercises, model compositions, dictation exercises, and outlines of British history. The fifth reader addresses health of the body, plants and their uses, as well as quotes from and stories of great people.

The sixth book–which I now have the good fortune to own–contains word lessons and passages with sections on great inventions, classification of animals, useful knowledge, punctuation and physical geography, as well as the British Constitution.

The sixth book–which I now have the good fortune to own–contains word lessons and passages with sections on great inventions, classification of animals, useful knowledge, punctuation and physical geography, as well as the British Constitution.

The anonymous author of the prose selection “The Bed of the Atlantic” writes: “In the northern part of the basin there stretches across the Atlantic from Newfoundland to Ireland a great submarine plain, known in recent years as Telegraph Plateau.”

To help the scholar, definitions are provided for such words as “ascertained,” “garniture” and “gossamer.” For those who desire elaboration of “Telegraph Plateau,” it is defined this way: “So called because on it were laid the submarine telegraph cables between Ireland and America in 1865 and 1866. Many other cables now follow the same route.” Questions follow. Of what does the end of the ocean consist? What part of the Atlantic has been surveyed? What plain stretches across the northern part of the basin? On what do the British Isles stand?

Longfellow’s “The Lighthouse” begins: “The rocky ledge runs far into the sea, / And on its outer point, some miles away, / The lighthouse lifts its massive masonry– / A pillar of fire by night, of cloud by day….”

There are two approaches to the vaunted Royal Readers. On the one hand, as Raymond Troke notes, “it seemed that everything had a moral lesson, and…everything was almighty gloomy…. By the time you got out of Grade 5 you knew a lot about death and destruction and had a powerful vocabulary to describe your miseries.”

On the other hand, novelist Bernice Morgan says, “The first literature I remember consisted of Bible stories and wonderful English ballads and heroic poems, which my mother read to us from her old Royal Readers.”

Jessie Mifflin recalls: “There were interesting and exciting tales in prose and verse in the old Royal Readers. We wept copiously over the death of little Nell, and exulted over the escape of the skater who was pursued by wolves in Number Four.”

The Royal Readers served a utilitarian purpose in those days. The reality was, as Mifflin adds, “Except for our textbooks, a dictionary, an atlas, and the Bible and hymn book for the opening exercises, there was no reading material in school–nor anywhere else, for that matter, except for the fortunate few who had books at home.”

my dad William Patey learn to read with the Royal reader I love lean a little bit about it Thank you Burton for sharing

LikeLike